Friday, December 22, 2006

Heh Heh

Thanks to Petrona for the link.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Christmas Quizzical

Who started a vicious turf war between paid-up members of Grub St and the bloggers?

Here are my Christmas quiz questions:

1. Since most bloggers I read reacted humorously or thoughtfully, where was the viciousness?

2. And who introduced the notion of exclusive territory, as replicated in those phrases paid-up and turf war?

I tell you, John Crace (who compiles the books questions) is my favourite bookish satirist of all...

Sunday, December 17, 2006

Campaigning Novels

In yesterday's Guardian Lucasta Miller writes about the recent discovery of a letter written by the Rev. Patrick Bronte soon after the death of his daughter Charlotte, which appears to disprove the established view that he was a domestic tyrant. Miller writes that it was Elizabeth Gaskell, Charlotte's biographer, who established this unfavourable reputation, demonising the Reverend in her attempt to present Charlotte as a victim and thus excuse what she considered the 'damaged imagination' which had given rise to what were seen as Charlotte's 'immoral and unchristian novels.'

I have been musing ever since why none of this surprised me.

Now there are many things I like about Gaskell, enough anyway for me to agree a few years back to write a serialisation of Mary Barton for Radio 4, and to work for a week on a treatment (until the BBC told my producer that sorry, their mistake, wires had got crossed, but there was already another writer-producer team working on the same project). And one of the things I like about her is her campaigning zeal. But the fact is that a campaigning zeal is not unproblematic - for a biographer (warping and supressing the facts in service of the campaign to improve Charlotte Bronte's image) or for a novelist either.

Gaskell's own biographer, Jenny Uglow, makes much of Gaskell's belief in stories (her biography is subtitled A Habit of Stories). Discussing the writing of Mary Barton, she says: Gaskell knew that stories had a persuasive power beyond that of rational exposition. However, the very wording of this sentence reveals Gaskell's view of stories as a means to a different end, in this case the (undoubtedly laudable) campaign to illustrate the plight of the working classes.

I know many people who love Mary Barton unreservedly, but all of these people are and always have been middle class. For some of us who hail from rather lower orders it's hard not to read this book without a sense of the sentimentality with which the characters are depicted, or a knowledge that this was a book written for the middle classes, or to get through the following passage without a sense of exclusion:

...what I wish to impress is what the workman feels and thinks ... there are earnest men among these people, men who have endured wrongs without complaining...And, frankly, I find the novel schematic.

I feel similarly about some of the feminist novels of the seventies and eighties (excuse me now while I don my asbestos suit), in which organic aesthetic concerns were subsumed by a political voice - which is a hard thing to say because it risks seeming to endorse the view that all feminist novels were so.

But before someone writes and points it out, yes, I was on the judging panel the year Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories won the Portico prize - a work of impeccable scholarship and warmth which presents Gaskell in all her complexity. And, hey, I did love the TV adaptation of North and South not so long ago...

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Never so Bad

Here are their categories: Theatre, Film, Visual Art, Music (divided into four sorts, each of which forms a category of its own: Jazz, World Music, Classical and Pop), Dance, Architecture, TV.

Books? No Books. There hardly ever is in these things. Why? Why don't books (at least books of creative writing - those potential categories Novel, Poetry or Short Stories) qualify as 'Art'? Are they any less 'art' than, say, Pop or TV? Or is it, on this occasion, that the compilers believe that in the world of books we haven't had it so good this year?

Or is it that art means entertainment now and words, unlike pictures and sounds, are just too damned abstract, or even too much like damned hard work?

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Normblog Writer's Choice

Saturday, December 09, 2006

The Bitch Is Not Top of the Class in Reading

You know, when I go to her site and to those of all those other omnivorous readers, something tightens in my stomach: that very same feeling I used to get when I stood on the sidelines and all those mega-athletic types ran the hundred metres etc. I feel inadequate, and because it's books, and because as a writer I'm supposed to be a well-read type, I feel guilty about it too.

It's pathetic, I know, but I just don't find reading books all that easy. They can take me over. They can affect me in such a way that they fill my mind, colour everything, they can even change me, as both a person and a writer. It's like a love affair in fact, it really is: if I like a book, I'm transported, I day-dream it, with no eyes for any other, sometimes going over its imagery and language for days, or even weeks after I have put it down. For this reason, as I have written on my other blog, it can be quite lethal for me to read while I'm in the middle of writing something myself. And in a way, if books don't do this, for me they're not really worth reading . It's precisely the effect I would love to be able to have on others as a writer.

No need to tell me: Bitch as I am, I'm also pretty weedy.

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Orwell and the Plain English Campaign

No doubt the PEC would pull me up on that first sentence for its length, long sentences being one of their bugbears. And do you know, I have a hunch they would be right. Maybe the facts packed into it would be clearer and more quickly assimilated if I separated them. But the fact is, I can't be bothered to go back and do this because of the time and thought it would take without making it clumsy, and I've got a damned play to write. This is one of Orwell's points: that writing more simply yet with a satisfying rhythm takes time and thought. It's easier and lazier to pick up on euphonious ready-made constructions (which tend to be abstract and convoluted), and when we do this we tend to write with less thought. Orwell expresses an opposite idea to the one that to simplify language is to dumb down: by providing a translation of a Bible passage into modern-day speak he demonstrates that the simpler, more concrete language of the original is far more vivid and thus more meaningful.

There are some odd apparent inconsistencies about the PEC. It's very off-putting to me that that arch mangler of the English language, Tony Blair, is one of their supporters - the guy who has so dramatically mouthed (as if it's his own coinage!) one of the very cliches Orwell condemned all that time ago: stand shoulder to shoulder. But then (to unpick another cliche) you don't necessarily blame the bandwagon for those who jump on it, do you, and it's the vice of our age (so well demonstrated in Animal Farm) to lump together everything a person says as either good or bad, simply because of who they are. And just because the application of a set of principles is not always successful does not of course mean those principles are wrong. Anyway, some of the PEC's examples of clarification don't seem so bad to me:

Before: High-quality learning environments are a necessary precondition for facilitation and enhancement of the on-going learning process.

After: Children need good schools if they are to learn properly.

I have to say, the first of these is the kind of thing I have satirised many a time in a radio play.

However, the thing which discredits the PEC for me is what seems to be a huge category error. Not content with the rightful target of officialese, at the end of their section on 'Long Sentences' they provide a list of creative works with exceptionally long sentences, including Ulysses (for Molly Bloom's long stream-of-consciousness monologue). It's not altogether clear that they are condemning them and that they have no notion that these long sentences are artfully constructed for specific and dynamic effect, but it looks like it (and anyway, I thought they were all about clarity?)

Nevertheless, I think that Orwell's six rules for writing English are useful for creative writers, and I have always tried to abide by them myself whatever I'm writing (not always successfully, of course, as that redundant 'myself' proves!). It's perhaps worth repeating them here:

i) Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii) Never use a long word when a short word will do. (This does not preclude the notion that sometimes a short word will not do.)

iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, cut it out.

iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday equivalent. (Once again, this does not preclude the notion that there may not be an equivalent.)

vi) Break any of these rules rather than say anything outright barbarous.

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

Little but Large

Today the Guardian announces that the winner of its first book prize is A Thousand Years of Good Prayers by the Chinese writer resident in the US, Yiyun Li.

Now I now that this book has not come from nowhere - it's already won several major international prizes, including the PEN/Hemingway award - and that the political import of these stories will have helped in this, but these are SHORT STORIES, for goodness' sake.

For years now the short story has been in major decline in Britain, to the point where it's almost dead, and I began this blog lamenting this fact. It's years since the fact that short stories don't sell became established publishing wisdom and many British writers - including me, originally a short-story writer - were forced away from short-story writing into other forms. It's years since, squeezed by market forces, the British print literary magazines, the last great haven of the short story, more or less disappeared (online magazines having yet to achieve the same kind of reputation with the literary establishment). (As I've written before, I've had my own attempt to combat this last decline, but found the battle so hard it left me no time to write.)

Depressingly, I've seen a more general contempt for the short story increase down the years, and signs that people no longer know how to read them. My reading group, for instance, won't touch them: they're not satisfying, some of the members have complained, you can't sink into them like you can with a novel, and anyway how could you discuss a whole book of different stories? They had not entertained the idea that a single really good short story could take as much time to discuss as a novel.

Now wouldn't it be nice if this award meant the turning of the tide?

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Plain Mystifying

The first attribute of the art object is that it creates a discontinuity between itself and the unsynthesised manifold.'The unsynthesised manifold', as Greer explains in her more recent article, is a phrase from Kant's Critique of Judgement which should be familiar to students of aesthetic theory, and Greer says, to 'most reasonably educated Guardian readers'.

Now I agree with those who have said that the PEC are barking up the wrong tree here (legalese and political obfuscation are surely the better targets), and it's also true that, as Ms Baroque illustrates with examples from their web site, there is a dangerous linguistic dumbing-down tendency in their philosophy and practice.

But, I don't know... Maybe it's the ex-secondary-school teacher in me, a teacher of rehoused Gorbals kids who had arrived at secondary school at the age of twelve unable to read... Those contemptuous sniggers when I didn't make myself understood, those life chances which failure to understand meant those kids wouldn't get... Maybe it's the ex-twelve-year-old in me whose uneducated relatives looked so dismayingly uncomfortable when I used big words they didn't understand... But, the thing is, I'm not very happy with that elitist supposition about 'most Guardian readers', Greer's assumption (in her original article) that she had no need even to say where that phrase comes from, leave alone what it means.

It's all a question of who you are writing for, I suppose. Are you writing only for those who already understand everything about the subject you're addressing, or are you prepared to include those who don't?

Sunday, December 03, 2006

What a Joker

Bloggers are the codgers who used to write letters in green ink banging on about speed humps or Judao-Freemason conspiracies, he writes green-inkishly, in a piece in today's Observer entitled 'Leave us some moron-free zones'.

They probably include gifted amateurs, he concedes, after a week of debate in which many have pointed out that plenty of professional thinkers blog - that wicked probably indicating that he hasn't bothered to look anyway. And slyly he manages to both misrepresent the motives of most bloggers and pander to the newspapercentric view of them as a threat by suggesting that the blogging of these 'gifted amateurs' might earn them what he codgerishly calls a proper job.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Our Treasured Fourth Estate

Monday, November 27, 2006

Clarity

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Simpering Bitches

Were you all avin a larf?

One thing you can say about writing for print publications: at least you get a copy editor to save you from yourself.

Cooke's view of blog reviews is clear from the title: Deliver Us From these Latter-Day Pooters.

As I have written below, I have my own reservations about a culture of recommendation without careful analysis, but I seem to be being held up as one of Susan Hill's main supporters on positive reviewing (see the Guardian Arts blog). A real first for The Bitch: never before in her life has she been identified with 'simpering acolytes'.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

What Do We Mean by 'Critical'?

The word "critical" doesn't have to mean "negative" - it can also mean "expressing or involving an analysis of the merits and faults of a work of literature, music, or art". I think "I like it" or "I don't like it" can be of some use, but if a reader discusses a book in terms of what the author was trying to achieve - whether the book succeeded in that project, how its various elements operated - it might never be necessary to say "I hated this!"

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Blog Reviews: Trust and Silence

Much has been made by both Sutherland and bloggers of the need to be able to 'trust' a reviewer's opinion, but I find this stance pretty suspect, if not elitist. One should never assume that a reader will 'trust' your opinion as a reviewer; in my opinion one should always review with the acknowledgement that one could be wrong. As a reader too, I feel the same: I want to be given the chance to make up my own mind, and I can't if a book is never even mentioned (and I don't happen to know about it). What's most important is the airing of opinions - debate, discussion. In my reading group people often change their minds about a book after an evening's discussion, or even about the question of what books are for. (For an example of this see our latest discussion.)

Monday, November 20, 2006

Saturday, November 18, 2006

Sutherland, Logic and the Bloggers

Although I do have my opinions about newspaper reviews, I haven't in fact voiced them so far on this occasion. The thing which concerns me is the lack of logic (or knowledge) which appears to be leading Sutherland to assume that (at the risk of repeating myself) all blog reviewers are untrained, that all untrained reviewers are not be trusted, and that readers cannot be expected to discriminate between good and bad reviews (or biased and unbiased reviews) and should therefore only trust the establishment (his word), ie newspaper reviews.

As it happens I think, like Scott Pack, that there is a place for both types of reviewing. Much has been made by bloggers in this debate of the fact that web reviews are written by 'book lovers', which I think can lead to a tendency towards positive reviews. This is of course a generalisation, and there are critical reviews on the web, but I know that many people think that recommendation is more positive and healthy than detraction. Personally I am interested in looking carefully at how books do and don't work, and so think that there's a place for the critical and (potentially negative) review - which newspapers do give space to.

Maybe this is all that John Sutherland was trying to say, but an injudicious phrase or two swept him away into the fury (and derision!) of bloggers. He did sound uncomfortable, I thought, on Radio 4 and further divested of his characteristic incisiveness and logic.

Friday, November 17, 2006

Welcome to an Orwellian World

On reading Susan Hill's blog about newspaper books pages, the literary editor of a national newspaper has emailed her to say that no books she publishes or writes will now be reviewed by that paper! (She won't name him/her.)

And, as Scott Pack points out, John Sutherland on Radio 4 was claiming the high ground of impartiality and ethics for newspaper reviewing! Surely it's a joke. Surely our worst suspicions haven't really been confirmed. Surely we're not really in that Orwellian world....

Getting Bleaker...

Thanks (I think!) to Debi for the link.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Scott Pack on the Today Programme

May have been the fault of the interview context (the brevity, and Humphreys drummming up controversy) but in accepting Humphreys' implication that all bloggers are untrained and then adding his own assumption that all untrained commentators have nothing of value to say, as well as appearing to believe that the readers of blog reviews have no ability to discriminate between good ones and bad, Sutherland was guilty of just the kind of lack of thoroughness of which he's accusing us all.

Scott says he's listened to the clip again and seems to think I'm being a bit harsh. I can't listen on this stop-gap laptop, so I'll have to leave you to judge.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

What Is Theatre For?

Last night I went to Manchester Library Theatre to see Too Close to Home by Rani Moorthy, produced by Rani's own theatre company Rasa, in association with the Library Theatre and the Lyric Hammersmith. Now I like the Library Theatre, if only for old times' sake, and but there is a bit of a corporate dead hand over it all - the theatre space is often slightly cold (conjuring unmagical images, even as you seat yourself for the hoped-for magical experience, of the council boffins sending out memos about the heating to the poor old creatives) and the white wine is frankly crap. (God, I'm getting old. Time was when I dismissed people who cared about the wine as small-minded old lushes.)

I shouldn't moan though: more often than you'd expect in this ambience, the productions are inspired (last year's Much Ado, directed by Chris Honer, for instance), and there is something really homey about the way Chris, the theatre's Artistic Director, always mingles with the audience in his baggy trousers and pale jackets and with his truly twinkly smile. And I get free tickets to Press Night, for godssake (I'm not sure why: maybe because I was once a member of the Theatre Writers' Union, but more likely, in these more commercially-corporate times, because I once edited a glossy-looking magazine).

Rasa have become best known for Curry Tales, also co-produced with the Library Theatre, the one-woman show in which Rani told global stories while actually cooking on stage, and which was also apparently broadcast on Radio 4 (I'm not quite sure how that would have worked, but then they do it on The Food Programme all the time,) and for their on-stage fusion of western-style dialogue with Asian music and dance. In view of all this, and the fact that the advance publicity indicated that the play would portray the family of a young suicide bomber, Too Close to Home promised to be explosive in more senses than one.

Well, firstly, though I am accustomed to seeing plenty of theatre people I know at Press Night, THERE WAS ONLY ONE: playwright Rina Silverman, and she had paid. What did that mean? That all the others were so uninterested in this burning issue that they couldn't get up off their arses even for a free ticket? That usually they only come to see their friends on stage (few of them are Asian)? And WHAT DID IT MEAN ABOUT THE POWER, OR OTHERWISE, OF THEATRE, TO REACH ACROSS A CULTURAL DIVIDE?

And as for the play. Oh well. Groan. I am going to have to say it: it left me cold. COLD, COLD, about this BURNING ISSUE!!! Oh, did I get weary with the wordy, wordy, 'western-style' dialogue, and I couldn't hear a fair bit of it (either the blocking was poor or the actors were occasionally swallowing their words), and, because so much of it was relating and recalling and telling, this really mattered, and, although I was meant to I didn't find it funny, and oh god, I DIDN'T UNDERSTAND. I never felt that I had any real insight into the mind of the young suicide bomber, and if this was the point, that, just like the real families of suicide bombers, the family didn't either, then it JUST WASN'T ENOUGH FOR ME, not in a two-and-a-half hour play with all that investment of creativity and time and attention, and BECAUSE IT SEEMS TO ME THIS IS THE BIG THING WE REALLY ALL DO NEED TO UNDERSTAND. But even allowing for this, acknowledging, say, that the focus of the play was the emotional effect on the family, well, I didn't understand the family either: I didn't find that the religious passion of the elder brother resonated (and believe me, I know about religious passion), I had no idea why the father had gone mad, either in terms of fact/plot or in terms of the theme of the play (except, as the Partner of the Bitch said, in order to become sane at the end), I was completely stymied by the sexual attraction between the elder brother and his aunt, and as for the mother, the main part played by Rani herself: I just didn't get her, crying one minute, grinning her head off and playing the clown the next - the whole family, in fact, quarrelling then hugging and joking in a way which seems borrowed from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? - but with nothing like the same conviction or forward momentum beneath the emotional see-sawing.

Hardly for one moment was I able to forget that these were actors acting on a stage. It's the worst criticism. Plays are meant to transport you, to take you into their worlds, and this play, with this subject matter, needed to do that especially. In one 'comic' moment, the mother is shouting at a neighbour for putting pork into her dustbin. She storms out to him, and in order to facilitate her exit, the huge fridge door becomes briefly an outside door. A line of Asian schoolgirls with their teachers gave a great spurt of laughter, a response I don't think was intended, and it was the only outright laugh the play got.

Oh dear. Was it me, was it the play, was it the theatre: I was physically cold, too, and had to put my leather jacket back on. All I know is, I wasn't transported, and that's what theatre has to do if it's to affect people's minds. We left the theatre quickly, as one does when one has been disappointed in a play, slightly deflated. When we got outside, the streets were glossy with rain and reflected lights, the Partner remarking with satisfaction, 'Typical Manc', and it lifted our spirits. We had already forgotten the leaflet for the play, featuring an intent young man carrying a rucksack through exactly the same night-time Westernised scene.

Oh, and half-way through the play The Partner of The Bitch fell asleep.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Furious Bloggers and Frightened Mandarins

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Where Did I Really Go?

Because I had to write about it when I got back, the book I took with me was Wuthering Heights, and for the whole week thus experienced a perpetually fluxing culture shock.

At Manchest airport I begin my re-reading, and I'm plunged into a world of horses, candles, and roads so small they disappear beneath snowdrifts; I look up and the planes on the runway fill my view.

Mr Earnshaw: I'm going to Liverpool today... I shall walk there and back; sixty miles each way.

The pilot's voice in my ear: We will be in Mallorca in two-and-a-half hours.

Lockwood falls into snowdrifts, people banished from the Wuthering Heights kitchen fire shiver in the unheated rooms, the moors are winter-bare; outside the airport, between the palms, the air is balmy.

I lie on my hotel bed: Nelly Dean must run for the doctor; my mobile phone goes, a call from home. Hareton and Heathcliff serve up porridge; I put down my book and stroll out for tapas.

Yet every single time I picked it up the book enclosed me in its world. The power of fiction, eh?

Monday, October 30, 2006

To Hell With It

Thursday, October 26, 2006

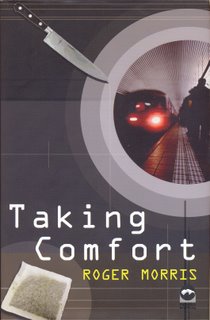

Taking Comfort by Roger Morris

It's Rob's first day in his new job. On the way into work, he sees a student throw herself under a tube train. Acting on an impulse, he picks up a file she dropped as she jumped. Over the next few days, he's witness to other disturbing events, some more serious than others. From each one he takes a 'souvenir'. As his behaviour becomes increasingly obsessive, he crosses the line between witnessing disasters and seeking them out, and events begin to spiral out of control.Hm. Sounds a bit like a thriller and not, therefore, quite The Bitch's cup of tea, a very different sort of thing from the brilliant psychological story by the same author, The Symptoms of his Madness Were as Follows which she once published in metropolitan, her literary magazine. Though that, too, was about a man with an obsession... So let's give it a go.

The bookseller holds it up (The Bitch has had to order it) and the dustcover confirms the impression: those dun greys, those fine lines like the crosshairs of a gun's sighting, that view of the tube station similarly circled, the blood-red lights of the train intimating violence and death, that minimalist collage of what seem like mystery/thriller clues: the knife, so iconically thrillerish, pointing towards that unsettling scene, but then the stranger teabag with its cosier Agatha-Christie-type connotations. The typeface: angular and sans serif mainly, though curiously not entirely, but on the whole at odds with its message 'Taking Comfort' - though, The Bitch thinks, carrying home the black shiny Waterstone's bag, comfort is perhaps what people read thrillers for: the comfort of the familiar mode, the comfort of violence packaged and dealt with and formulated - precisely the things which make her impatient with the genre.

The bookseller holds it up (The Bitch has had to order it) and the dustcover confirms the impression: those dun greys, those fine lines like the crosshairs of a gun's sighting, that view of the tube station similarly circled, the blood-red lights of the train intimating violence and death, that minimalist collage of what seem like mystery/thriller clues: the knife, so iconically thrillerish, pointing towards that unsettling scene, but then the stranger teabag with its cosier Agatha-Christie-type connotations. The typeface: angular and sans serif mainly, though curiously not entirely, but on the whole at odds with its message 'Taking Comfort' - though, The Bitch thinks, carrying home the black shiny Waterstone's bag, comfort is perhaps what people read thrillers for: the comfort of the familiar mode, the comfort of violence packaged and dealt with and formulated - precisely the things which make her impatient with the genre.He is a marketing man. A phrase which recurs, a litany inside Rob's head, like other phrases, and phrases in the heads of other characters, replicating the psychology by which we maintain our tenuous hold on reality, and our sense of safety. The Bitch appreciates the poetry of this prose.Robust stitching and lined with a cotton material Flapover conceals triple sectioned interior pus pockets on front Size 44 x 33 x 14cm

He is a marketing man. He can appreciate the abrupt punctuation-free poetry of that copy.

In his hand, you have to imagine how it feels, the Di Beradino classic briefcase... The whole focus of his being is in the grip of his hand around that hard leather handle, in the way the seam stubs into the underbellies of his fingers, in the swing of the handle in its sold brass satin finished fittings. In the sense he has of its contents and how they influence the swing and how that swing uplifts him.This is how we 'take comfort', how all of the novel's characters take comfort, pinning their fears and desires on certain objects - Rob's wife Julia on her particular brand of cooking knife, the Sabatier Au Carbone 8 inch Carbon Steel Chef's Knife (the knife on the dustcover), the receptionist on her Twirl mug - their psyches/identities and the objects becoming intertwined. And the form of the book replicates this perfectly, each short chapter being named for a branded object, and each moving forward the action through a character's relationship with that object.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Living Through the Kids

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Glittering Inconsistencies

There was a time when, as Wordsworth wrote, 'Every great and original writer, in proportion as he is great and original, must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished.' The culture is no longer so patient. In a time of information overload - of cultural excess and superabundance - our taste is being increasingly created for us by prize juries and award ceremonies... Prizes create cultural hierarchies and canons of value. They alert us to what we should be taking seriously: reading, watching, looking at, and listening to. We like to think that value simply blooms out of a novel or album or artwork - the romantic Wordsworthian ideal. We would like to separate aesthetics from economics, creation from production. In reality, value has to be socially produced.I think Cowley hits the nail on the head here, but I also think he seriously weakens his own argument by taking to task Martin Amis and Phillip Roth for purporting to despise prizes yet nevertheless being in thrall to them. Amis, he says, for all his elevated disapproval, is preoccupied perhaps more than any other writer of his generation by the larger literary game, by who is winning and losing, and goes on to cite Amis's novel on the subject, The Information. As for Roth, a writer known to take an active part in his own jacket designs, Cowley calls him 'disingenuous' for allowing himself to be represented on his latest by merely a long list of prizes won, an act which Cowley calls 'an exercise in self-aggrandisement'.

But surely, in relation to Amis, the point is that it is those who fall on the wrong side of a cultural situation (Amis is famously not a prize-winner) who know best its iniquities (and will be obsessed with them)? And if, as Cowley says, prizes have a stranglehold on our culture, then an understanding of the iniquities does not free anyone, including Roth, from the trap. Cowley thinks there is a sense of presumption in not noting where or when the writer was born: as if to say, 'You know exactly who the famous and excellent Philip Roth is, he needs no introduction.' Instead, we are told only what he won, as if past achievement validates the present offering. Well, excuse me, but, against the grain of the cult of personality, I think a writer's literary history is more important than his personal one...

But then at the end Cowley tells us this about the prize culture: ...it shouldn't be taken too seriously, and one wonders how serious he himself is being. This is his reason: no one now has heard of the first Nobel Literature prizewinner, Sully Prudhomme, who won that year over Tolstoy. But, to take his earlier argument further, it's a different culture now. In this era of remainders and the slashing of backlists, would Tolstoy's books remain on the shelves nowadays long enough to become classics, or would they have been binned, as he tells us Lionel Shriver's were before she won the Orange Prize?

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Tagged, Memed, Caught Out Again

Last week Debi Alper, who has a fabulously witty blog, tagged her thus: Five Things Feminism Has Done For Me. Well, this is what feminism has done for The Bitch:

1. To make her stick to her own agenda (fiction and publishing, not feminism!).

2. To make her set her own rules (five things be blowed).

Today Roger Morris zaps her: Eight Things About Me.

What???? Well, here goes:

1. Far from wanting to reveal eight things about herself, The Bitch would still be anonymous if Blogger hadn't undone her (for The Bitch's anonymity was in part an attempt to underline her view that in our present cultural climate words and ideas are subverted to image and personality).

2. Even on her writer's blog The Bitch tries to stick to professional matters, though she knows she's not successful, and anyway being professional means using images etc in just the way she critiques here.

3. The Bitch once ate for breakfast a literary agent who wanted to sell her fiction as autobiographical.

4. The Bitch once ate for tea an editor who ditto.

5. The Bitch keeps a bullwhip ready for when newspaper journalists come calling and ask to go to the loo and go through your cabinet.

6. Schooled from the age of five, The Bitch has never, ever allowed anyone to misquote her

7. or judge her work by her life.

8. The Bitch is a writer of fiction. (Geddit?)

And now I'm supposed to tag someone else. How about Ms Baroque, Fessing Author, Alias Lucy Diamond , nmj, and Bournemouth Runner at The Art of Fiction (and they can choose either meme or none at all..)

The Bitch Munches her Words

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Thanks for Sharing

Last night she went with The Partner to a reading by the Irish poet, playwright and novelist Sebastian Barry. Now Barry to The Bitch's mind is a quite brilliant writer, a writer after her own heart, one of those you read and get the quite spooky feeling that he's written what you might have written, or would have written if you could/in another life, or already once did in a previous life etc, etc. Turned out he's a brilliant reader as well, which so few novelists are, and The Bitch was bewitched, and, as he read from his latest novel A Long Long Way, laughing and in tears.

Then he turned to one of his plays and read a long tale-telling speech from near the end about a dog and a ewe, which he pronounced, exactly as the Bitch's Irish father did, 'Yo'. The Partner gave The Bitch a nudge, and she knew what he was thinking: about the tale her father always told of the time he was eight years old but not at school because his parents were so poor, and the schoolmaster happened by and asked him if he could spell ewe, and he could, so after all he went to school, paid for by the church... It's one of those little incidents from real life I've pleated into the made-up rest of a novel of I've just written.

Well, then I went to get my copies of Barry's books signed, and I told Barry what a brilliant writer I thought he was, not caring if he thought I was a suck, and he looked ridiculously pleased, and it was like some kind of literary love-in. And then The Partner, who was standing right beside The Bitch, said,'Tell him about your father's ewe.' For god's sake! (These people at signings, wanting to come up and identify, and tell you their life stories!) But Barry was looking curious now - or was that glazed? - and out of embarrassment, The Bitch told him.

A strange look had come over Barry's face. 'What church was that?' he wanted to know. 'What town was it?' The Bitch answered in embarrassment, feeling possibly patronised - for god's sake, it was meant to be just a throwaway anecdote! She began to leave (to make a hasty retreat) and Barry said, his face impassive: 'Don't be surprised if you come across that incident in the next thing I write.'

The Bitch jumped like a scalded cat. 'You can't! I've just put it in my novel!'

'We'll just have to see who gets there first.'

'But that's not fair! You've got a publisher, and I haven't yet!'

His face was bland, beatific. 'It never is fair.'

'Bastard!'

His grin was impassive, enigmatic.

I think he was joking (why the hell would he want my silly little anecdote?). But just in case: YOU READ IT HERE FIRST.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Voices and Ears

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Uncreative Writing

Interviewed today in the Guardian by Laura Barton, Booker winner Kiran Desai points out one of the problems: They demand you write a certain way because you have to present your work in half-hour instalments. You are having to polish only a little bit of it. It suits the short story more than the novel. She could never have written her 'monster' novel under these circumstances, she says.

The Bitch has often guiltily thought that it's nigh on impossible to write any novel under these circumstances. In particular, novels which play narrative games with readers' expectations simply don't lend themselves to the piecemeal week-by-week judgement of others' expectations. But for any novel to be unified and organic, you usually need to get to the end before you can know precisely how to hone the beginning, after all.

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Too much experience?

...the publishing market treats novelists as promotable contenders with their first and second books, mature talents by their third, and burned out with their fourth and subsequent titles. This year's passed-over favourite, The Night Watch, was a fourth novel [and from the only established author on the list].

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Short and Sharp

http://books.guardian.co.uk/digestedread/story/0,,1891754,00.html

Monday, October 09, 2006

A British Sporting Event?

The winner is JM Coetzee, with Disgrace (in good old colonial style The Observer, 'following the Booker', decided to define 'British' as including 'Ireland and the literary traditions of the Commonwealth'); 2nd place goes to Martin Amis's Money, and joint third to five novels: Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess, Ian McEwan's Atonement, Penelope Fitzgerald's The Blue Flower, Kazuo Ishiguro's The Unconsoled, and Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children. Joint eighth place is shared by Ishiguro (again) (The Remains of the Day) and John McGahern with two novels, Amongst Women and That They May Face the Rising Sun.

This is not a readers' poll. If this poll has any consequence, McCrum opines, it derives from the fact that we have consulted with mainly professionals. Ah, that best of British... Those polled were writers themselves and critics. Well, I have recently argued that writers are excluded from debate about the meanings of their work, but this is not that kind of debate. It does not appear to be much of a debate at all, but just another of those winners-past-the-post British exercises, pitting different kinds of writing against each other in the pursuit of some kind of mythical pinnacle.

What does it all mean? McCrum feels that his wider trawl through the 'Commonwealth' makes The Observer poll more culturally inclusive than the similar American poll conducted last spring, but putting culturally diverse writings in competition with each other, in which some will 'win' and some won't, is surely to operate exclusivity. I notice some names missing from the list of those polled - apparently some declined, for these sorts of reasons - and isn't it obvious that writers, understandably, might well gun for the kind of writing which includes their own? (One would never want to accuse anyone of voting for their friends, of course!) And does it mean anything that, although the list of voters is almost half women, only one woman makes it to the first eight, and out of 51 runners-up only 18 are women? (What, so it's true, then: women's novels are less good than men's? Or no: women novelists are still in awe of the men while the men aren't so thrilled by the women? Which?)

And some of the names missing from the list of voters? Well, actually, JM Coetzee, Martin Amis, Ian McEwan and Kazuo Ishiguro. Is there some kind of poetic (or novelistic) justice going on here?

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Rub those pound signs out of your eyes...

http://www.gawker.com/news/unsolicited/unsolicited-why-you-dont-want-a-big-advance-203569.php

Thursday, October 05, 2006

Selling Words

fancy photomontages:

fancy photomontages:  and towards the end, big bleed photos:

and towards the end, big bleed photos:

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

How to Sell a How-To Book

Taylor's main point is that these books, aimed in the main at reading groups, reinforce, through their choice of novels for discussion, 'the stranglehold exerted on literature by the three-for-two promotion and the high-street discount'. Thus, he says, they contribute, in a way which would probably horrify their authors, to the 'homogenisation of our literary culture.'

He has a point, I think. The Bitch is in a reading group whose members pride themselves on being immune to hype, and on forming their own opinions without recourse to others - black looks for any fool who brings to a meeting reviews downloaded from the internet. But if these How-To books would never sell to my lot, they are clearly selling to someone. And anyway: which books come to mind when my independent, stroppy lot are thinking of books for discussion: why, the Booker shortlists, of course, the books they've seen in three-for-two promotions - they're the only ones they can be expected to have heard of, after all.

And if these How-To books didn't feed into the expectations of reading groups, how would they sell?

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

Don't We Just Love a Scapegoat?

As an agent, I feel quite strongly that Frey was shafted by his publisher and agent. Not only must they have known that embellishment was going on, they *did* know - I met an editor at Doubleday who told me, prior to the book's Oprah laurels, that he was sure some of the book wasn't true. It is deeply disingenuous of the professionals closely involved in the book's publication to claim they were duped by Frey, ruthless of them to drop him, and deeply immoral for them to continue to profit from the discredited works which they are merrily doing.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Authors and Authority

The event was a prize-giving, the culmination of a competition run by an organisation whose main activity is running short courses and workshops for writers. A founder tutor and competition judge announced the prizes, in some cases inviting the author to read, and in every case talking in some detail about the winning work.

My artist guests were both fascinated and shocked. Firstly, they were fascinated by the thing I have always taken for granted, the spectacle of authors getting up and reading out their work aloud, sometimes with confidence, sometimes visibly shaking, sometimes reading well and sometimes not so well. What struck them forcibly, as contemporary artists trained to create work in such a way that it speaks for itself, was that the author was thus forced to be in the way of the writing, and the writing itself thus subsumed and ultimately divested of authority. This is obvious when the reading is bad, but it's true even if the reading is good, and of course it's true even at a famous author reading, where the whole thing plays into the cult of personality.

More importantly, however, the thing which shocked the artists was the compere's commentary. Trained in London art schools to take full responsiblity for the meanings of their work and, to that end, to control the context in which it appears, they were staggered that writers could be in a position where another person could decide independently what their work was about and announce it to the world, while the author had no opportunity for speaking about his or her work. Well, I laughed at the time, the judge was after all saying pretty nice things, and I was one of the winners, and it doesn't do to look a gift horse in the mouth, but it's true that when he said my story was a 'rite of passage' piece I was pretty gob-smacked for a moment, and couldn't work out how he made that out, and later when I did it struck me that, much as he'd liked my story, he may well have missed the point.

And afterwards it set me thinking. Clearly we can never expect to have ultimate control over how our work is read - books are ultimately what readers make of them - and clearly sometimes authorial intention fails to be realised, but writers do sometimes do new things which need to be read in new ways. Yet it does seem that on the whole it is the writers who have least voice in any debate about their work. One of the biggest crimes, for instance, has always been for a writer to take issue with a newspaper criticism (so undignified!), and now, it seems to me, the whole creative-writing teaching explosion has led to an ethos in which the authority on the meaning of a writer's work is not the writer but another (the teacher). Interesting that while the teaching of art has so much longer a history than the teaching of creative writing, artists do not suffer this situation. And look at James Frey, apparently utterly without control of the context of his work, and when he tells the Guardian that he first wrote his book as fiction, he may as well have said it into the wind, for there's John Burnside writing in the same paper last week, making the argument I have made about different kinds of literary truth, but nevertheless overlooking this crucial point.

Ironic, really, when you think of why we write in the first place...

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

My Rochester, Your Jane

Time to read it again, I guess...

Monday, September 25, 2006

Novelists and wealth

Monday, September 18, 2006

Novels versus Memoirs

In the interview with Laura Barton, Frey makes this claim which tickled the Bitch's antennae: he says that initially he wrote the book as fiction, but that it was turned down by 17 publishers(including Doubleday who eventually published it), all of them asking 'How much of this is true?' and clearly in the market for non-fiction rather than fiction. Barton doesn't manage to ascertain at what stage the book began being touted as non-fiction - whether Frey made the decision himself before re-submitting, or whether the publishers were complicit in the transformation (Frey claims the latter, but his now ex-agent claims to have been duped by him).

Whatever the truth of this particular situation, it's extremely interesting that a fine writer, as Barton assures us he is (I haven't read the book), and a man who apparently longed to be a novelist, feels compelled to allow his work of autobiographical fiction to be launched on the world as a memoir, and exceedingly interesting that non-fiction is what sells now.

Laura Barton speculates that perhaps this latter 'is an indication that we are recoiling from a culture that has grown increasingly synthetic.' Yet, as I have argued before, it is good novels, with their particular universalising power, which are anything but emotionally synthetic, but have the real power of emotional truth. Perhaps the very reason that this book affected so many people so powerfully, was that it was indeed really a novel, with all the novelistic tropes and exaggerations and patterns which can so persuade the emotions.

Oprah claimed that, having identified so closely with the book, readers now felt betrayed. But could it possibly be that readers are in fact easier with the idea of a memoir because the experience in a memoir is safely identifiable as another's, and not our own as a good novel can make it? That the emotion evoked by a memoir is thus easier to handle, more safely sentimental?

And then we come to the Booker shortlist, only one of which I have read, Hisham Matar's In the Country of Men. Now this is a book with a very moving story - that of a nine-year-old boy in Gadafy's Libya, with a dissident father under threat of arrest and torture and an unhappy mother driven to illegal drink - and, in view of the current asylum-seekers debate, a story which needs to be told. The thing which strikes me about it, though, is that, like Khaled Hosseini's The Kite Runner (which has an interestingly similar cover illustration), it takes the form of a memoir, and to my mind it suffers from that. The narrative is constantly interrupted and slowed down and deprived of dynamism by memories related in the past continuous tense (we used to ...) (or whatever that tense is called nowadays), and towards the end there is a memoir-like filling-in-the-gaps exposition which I found indeed distancing (although the book is then saved by a very moving end).

Interesting that The Observer, reporting on the shortlist on Sunday, felt compelled to point out the parallels between the events of the novel and those of Matar's life, as well as those between Edward St Aubyn's book and life. Why are we so keen nowadays to see an author's life in their books? Cult of personality, as I so often think? Or retreat into the safety of the otherness of memoir?

Saturday, September 16, 2006

The Bitch Unmasked

Ah well, the anonymity was fun while it lasted (though some people had already guessed, and the clues were there), but there was a serious point. There is a long and honourable literary tradition of pseudonymity and anonymity, and for good reason. Although obviously it can be used for nefarious purposes - the personal attack on Scott Pack by The Observer's Browser comes to mind - it can also allow for clearer intellectual debate, a way of focussing properly on the issues.

Let me illustrate. A few weeks ago, one-time TV presenter Selina Scott was interviewed by The Guardian about her criticisms of contemporary television. One of Scott's main points was that older women are under-represented on today's TV. Scott, a willowy Diana lookalike (a fact which, as far as I remember, the article made a fair deal of) is now a woman of, shall we say, a certain age (but still a damn good-looker, actually!) And how did the interviewer respond to this statement of Scott's? By asking her if it were sour grapes! By focussing not on the issue - not inviting Scott to elaborate or prove her point or engaging in a debate about it - but on Scott herself, and in such a way as to invalidate and trivialise her point. And how did Scott feel forced to respond? By saying defensively that of course it wasn't sour grapes, she'd had plenty of opportunities - by which statement she was in great danger of disproving her point herself! The whole issue of women in television was thus muddied before being quickly dropped.

We're all familiar with the Victorian female novelists who adopted male pseudonyms in order to be read without prejudice, or indeed at all, and as I've indicated on my other blog, I've had my own experience of being silenced as a writer simply for being who people thought I was, or indeed for knowing the people I knew.

This blog was an attempt to interrogate that, and the anonymity was intended as an illustration of my point, the need sometimes in this age of obsession with personality to separate the personality from the message.

But you know who I am now. You can judge my comments through what you know about my life and own career. Ha! So hang me.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

This libraries problem...

'But don't you think the libraries have a place as social centres - now that there's no longer the church or the village hall?'

The Bitch choked on her Pinot Grigio and considered going home to pack her bags.

'In fact,' went on The Partner, 'social centres are precisely what libraries are not becoming. The shift to computers is just as isolating as silent reading rooms: more so. Wouldn't it be better, if libraries want to expand, that they expanded into activities centred around books?'

He had a point. The Bitch abandoned her plans for packing.

'Though, you know,' he said, 'I have a hunch that for a lot of people libraries were never places for fiction. Many people went to the library mainly for facts.'

The Partner works with people's problems. 'Even so,' he went on, 'in the old days no one ever came to me and said that they had been to the library and read up about their condition. But every day I get people coming to me and saying that they've looked it up on the internet. So you can see why libraries might shift towards computers...'

Hm.

'Also,' he said: 'this argument that libraries shouldn't abandon books because the expansion of the bookshops shows how much people love them and need them: well, couldn't that be an argument for the other side: people buy books now, so they borrow them less?'

Oh yeah. The Bitch's very own subject: commercialisation and commodification.

A bleakness descended over The Bitch. She decided to drown her sorrows and ended up pretty drunk.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

An Extra Large Slice of Cheer

In a comment on my post 'Big Slices of the Literary Tart' Susan Hill alerts us to that fact that 1,200 copies have now been sold of the first novel by Helen Slavin, The Extra Large Medium, recently published by Susan's press, Long Barn Books - when apparently 400 copies is normal for a first novel. On Monday I went out to buy it, and found it on a 3 for 2 offer in Waterstone's, which as far as I know is no mean feat for a small publisher. Yesterday I sat down to read it. I could not put it down. The dishes went unwashed, the writing I'm supposed to be doing went unwritten. I did not stop until I had finished, and when I looked up my eyes could no longer focus, literally, on the real world. This is some sassy book, written in a spare, witty and streetwise style, packed with word play, yet managing to tackle the serious issue of the nature of loss with the kind of interiority I value most in novels.

A small press, but an extra large, not medium achievement...

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Ideas as commodities

It's absolutely true that - as Jessica, Alan Kellogg and Susan Hill point out, and as the recent Dan Brown trial showed - there's no copyright on ideas, nor should there be. And that many great writers are great on the strength of borrowed ideas, and, as Alan says, Shakespeare is the biggest nicker of them all. Modern copyright only applies to text (in the broadest sense, including all the art forms), which is why, as Jessica, says, so many new writers rush around putting sealed envelopes in their bank safe deposits.

It all seems so simple. It's not. When does an idea become text? As Susan and Alan say, once it gets fleshed out with characters etc and becomes imbued with an author's voice. But according to the law, this has to be written down, and more fool you if you spend an evening in the bar with a famour writer telling him your plot. And what about what people can do with a text? That treatment you wrote, the storyline of which was cleverly enough distorted that lawyers might argue for days: the young boy turned into a young girl, the three separate but linking story strands brilliantly teased to make three separate episodes of a drama series (and thus losing the subtleties)? You might think that this makes the original treatment unrecognisable, and that therefore it doesn't matter, but you can bet your bottom dollar that the TV company wouldn't think so. A storyline about x? Sorry, it's been done... TV companies do not take the line that it's not the idea that matters but what you do with it, the way you write it. They are not interested in writing but in ideas as commodities.

This is what's at the root of the problem: the commodification of ideas and art. That offending clause I mentioned previously is based on the notion that TV companies can buy ideas off you, and not only ideas but ownership of what you've written, and they often do, sometimes replacing the writer halfway through the development process - another thing the standard contract allows for (and which my contract allowed for). The concept of copyright drops by the wayside in this scenario. In fact, it's the big boys who benefit from copyright law (how successful would I have been, rushing round and waving my little safe deposit box in the face of that big powerful organisation with Miss Ice-Cool TV Executive folding her arms at the door?). Which is why traditional copyright is now being challenged by the Creative Commons initiative, based as I understand it on the notion of making artists' work more freely available for acknowledged borrowing, and on a democratic melting pot of creativity in which one artist's work can enrich and generate that of another - but in which the operative words are acknowledged and democratic.

Saturday, September 02, 2006

The Bitch is a Dunce

Pray give me leave to tell you a tale of a Blogger-Boggled Bitch.

Once upon a time a Bitch was blogging happily away, her comment settings fixed at the default mode they came with - Registered Users only, Comment Moderation unticked - and with email notification ticked, comments appearing on her posts (and in her email box) now and then. Then one day (this week) Jessica commented on Scott's Pack's blog that she had wanted to leave a comment on The Bitch's blog, but hadn't wanted the hassle of registering. Quickly, The Bitch adjusted her comments settings to allow anyone to comment, and generously Jessica tried again and The Bitch was rewarded by hearing what she had to say.

Next, The Bitch gets a gentle hint from Alan Kellogg: he presumes she's checking comment moderation. Yikes! thinks The Bitch, completely misunderstanding and thinking he means tick when he says check and is warning her against junk and offensive posts now that anyone can comment, and she dashes to the settings page and ticks 'Comment Moderation'. Some hours later she opens the Comment Moderation menu, and lo and behold, what does she find but a long list of comments waiting for moderation, some of them dating way back, one person even wondering why the comment she posted previously hadn't appeared! (And since The Bitch was away from her broadband and using a mobile connect card and paying for every kilobite downloaded, and every one of those beeps was audibly chipping at her meagre bank balance, she went hot, started a migraine, and published the lot without loading them up, so that junk and offensive stuff got published anyway!)

The Bitch is still scratching her word-filled but technologically-deficient little head about this, and maybe someday some kind person of a more worldly-wise character will take her by the hand, sit her down and explain, but in the meantime, folks, a thousand apologies and thanks for all your insight and wit.

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Those slippery ideas...

Hm, says The Bitch, gnashing her teeth at the memory of what happened to her.

The Bitch thought the same as Jessica the time a freelance producer went down to London with a few of her ideas, all of which were duly rejected, only for one of them to appear as a well-received drama series a year later. You hear of it happening all the time, after all.

But she got a bit more cynical when, not so long ago, she went in for one of these New Writing Schemes run by a major television company and funded by the local arts body. She should have smelled a rat right at the start, of course - why would a major TV company need puny arts board funding to run such a scheme, which consisted of a single day of workshops with fees, presumably, to three well-known TV writers, a fee of £500 each to the fifteen or so participants to write a detailed treatment, and a big plate of sandwiches? Could it possibly just be to give the whole thing a veneer of worthy respectability? The project was supposed to be an investment for the company, after all: the stated aim was to look for new writers.

Ha. Well, I did smell a rat when I saw the contract. There was the clause which is apparently standard nowadays, based on Jessica's idea of a big Floating Tank of Ideas, stating that there was no come-back if my idea wasn't taken on but was later used by the company. But we were being asked to write detailed treatments, and were hardly being paid professional rates to do so... Was this really a cynical ideas-trawling exercise, and this time they were getting them on the cheap?

Well, true to form, The Bitch kicked up and tried to negotiate the contract, but she'd met her true match in the disgustingly young but steely woman running the show, who told her in no uncertain terms that the contract wasn't negotiable (did that woman own a dictionary?), that The Bitch had behaved pretty badly and joined the scheme in bad faith, and The Bitch was forthwith kicked off the scheme - without her £500.

Too late, like a fool she had already written her detailed treatment. And the real rat turned out to be not the company but a writer (as Jessica indicates): six months later the famous writer who read her treatment replicated in his drama series not only her storyline and theme but even the camera shots with which, in the workshop, he had been so taken. Well, maybe he did it subconsciously, and what's a Bitch to do, but take it as a compliment...

But you still wonder about the TV company. The writers on this scheme had all been chosen via stiff competition, all were of a professional standard and offered good ideas, and a series of six dramas was promised as an outcome. In the event, no series materialised. Only one of those ideas was produced under the name of a writer in that workshop, as a lone drama which went out about midnight when no one would be watching... perhaps to fulfill the conditions of the arts board grant?

Monday, August 28, 2006

Some joke, surely...

This week the Observer's 'Browser' pours vitriol over Scott Pack, former chief buyer for Waterstone's and now publisher with the online Friday Project, for starting his blog Me and My Big Mouth. Presumably someone sensible at the Friday Project will tell Mr Pack that it's his job to find interesting/amusing/informative new authors and not offend people with his tedious comments, says the Browser offensively (and under the tediously offensive title That's codswallop, Scott.) Impossible to believe that the Browser did not know that this would send us winging straight off to Scott's site to check this out and find not tedious comments but a chatty, personal, ironic and surprisingly self-deprecating tone, interesting insider's insights and among other things an informative and engaging post on literary magazines (which get short shrift in pages like the Observer). And in the process of course we are introduced to the Friday Project, so as Commercial Director, Pack is hardly failing to do his job...

And Pack alerted me to another site, The Age of Uncertainty, which I found I loved! Thanks, Browser!

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Newspapers, doncha just love em?

My parents [the Times columnist Libby Purves and Paul Heiney] are in broadcasting. Does that make things any easier? Only in the sense that it gives you a little comfort in leading a freelance life.The Bitch drops the paper. Is she kidding? Only in the sense that it gets you a two-thirds-page column with a colour photo (all that free publicity) in Mummy's paper!

And those brackets have alerted The Bitch to what she should have realised all along: that this is one of those dishonest supposedly first-person accounts a journalist has concocted out of an interview (in this case Dominic Maxwell). The Bitch now imagines the scenario:

Dominic (down phone): Rose, both your parents are in broadcasting. Does that make things any easier?

Rose (thinking, Oh god he would come up with that one! Now no one will think I have any real talent! Defensively, with heart sinking and imagining the reaction of readers like The Bitch): Only in the sense that it gives you a little comfort in leading a freelance life.

You can imagine the conversation which led to this airily smug little paragraph, which even while she understood what was going on made The Bitch sneer:

During the day I'm actually writing a novel... I've got an agent for it and we're hoping to sell it at the start of September.

It gets worse, though, much worse:

It's a difficult situation for me and my parents at the moment [Heiney's brother Nick committed suicide in June after suffering from depression for years] but I don't mind talking about it, it's such an elephant in the room. I didn't consider cancelling the show.At which point The Bitch was no longer sneering at Rose Heiney's apparent self-serving glibness but ready to bop Dominic Maxwell on the nose.