Monday, October 30, 2006

To Hell With It

Thursday, October 26, 2006

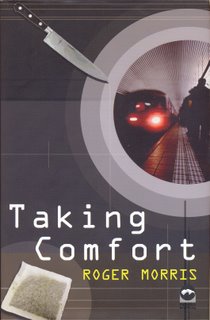

Taking Comfort by Roger Morris

It's Rob's first day in his new job. On the way into work, he sees a student throw herself under a tube train. Acting on an impulse, he picks up a file she dropped as she jumped. Over the next few days, he's witness to other disturbing events, some more serious than others. From each one he takes a 'souvenir'. As his behaviour becomes increasingly obsessive, he crosses the line between witnessing disasters and seeking them out, and events begin to spiral out of control.Hm. Sounds a bit like a thriller and not, therefore, quite The Bitch's cup of tea, a very different sort of thing from the brilliant psychological story by the same author, The Symptoms of his Madness Were as Follows which she once published in metropolitan, her literary magazine. Though that, too, was about a man with an obsession... So let's give it a go.

The bookseller holds it up (The Bitch has had to order it) and the dustcover confirms the impression: those dun greys, those fine lines like the crosshairs of a gun's sighting, that view of the tube station similarly circled, the blood-red lights of the train intimating violence and death, that minimalist collage of what seem like mystery/thriller clues: the knife, so iconically thrillerish, pointing towards that unsettling scene, but then the stranger teabag with its cosier Agatha-Christie-type connotations. The typeface: angular and sans serif mainly, though curiously not entirely, but on the whole at odds with its message 'Taking Comfort' - though, The Bitch thinks, carrying home the black shiny Waterstone's bag, comfort is perhaps what people read thrillers for: the comfort of the familiar mode, the comfort of violence packaged and dealt with and formulated - precisely the things which make her impatient with the genre.

The bookseller holds it up (The Bitch has had to order it) and the dustcover confirms the impression: those dun greys, those fine lines like the crosshairs of a gun's sighting, that view of the tube station similarly circled, the blood-red lights of the train intimating violence and death, that minimalist collage of what seem like mystery/thriller clues: the knife, so iconically thrillerish, pointing towards that unsettling scene, but then the stranger teabag with its cosier Agatha-Christie-type connotations. The typeface: angular and sans serif mainly, though curiously not entirely, but on the whole at odds with its message 'Taking Comfort' - though, The Bitch thinks, carrying home the black shiny Waterstone's bag, comfort is perhaps what people read thrillers for: the comfort of the familiar mode, the comfort of violence packaged and dealt with and formulated - precisely the things which make her impatient with the genre.He is a marketing man. A phrase which recurs, a litany inside Rob's head, like other phrases, and phrases in the heads of other characters, replicating the psychology by which we maintain our tenuous hold on reality, and our sense of safety. The Bitch appreciates the poetry of this prose.Robust stitching and lined with a cotton material Flapover conceals triple sectioned interior pus pockets on front Size 44 x 33 x 14cm

He is a marketing man. He can appreciate the abrupt punctuation-free poetry of that copy.

In his hand, you have to imagine how it feels, the Di Beradino classic briefcase... The whole focus of his being is in the grip of his hand around that hard leather handle, in the way the seam stubs into the underbellies of his fingers, in the swing of the handle in its sold brass satin finished fittings. In the sense he has of its contents and how they influence the swing and how that swing uplifts him.This is how we 'take comfort', how all of the novel's characters take comfort, pinning their fears and desires on certain objects - Rob's wife Julia on her particular brand of cooking knife, the Sabatier Au Carbone 8 inch Carbon Steel Chef's Knife (the knife on the dustcover), the receptionist on her Twirl mug - their psyches/identities and the objects becoming intertwined. And the form of the book replicates this perfectly, each short chapter being named for a branded object, and each moving forward the action through a character's relationship with that object.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Living Through the Kids

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Glittering Inconsistencies

There was a time when, as Wordsworth wrote, 'Every great and original writer, in proportion as he is great and original, must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished.' The culture is no longer so patient. In a time of information overload - of cultural excess and superabundance - our taste is being increasingly created for us by prize juries and award ceremonies... Prizes create cultural hierarchies and canons of value. They alert us to what we should be taking seriously: reading, watching, looking at, and listening to. We like to think that value simply blooms out of a novel or album or artwork - the romantic Wordsworthian ideal. We would like to separate aesthetics from economics, creation from production. In reality, value has to be socially produced.I think Cowley hits the nail on the head here, but I also think he seriously weakens his own argument by taking to task Martin Amis and Phillip Roth for purporting to despise prizes yet nevertheless being in thrall to them. Amis, he says, for all his elevated disapproval, is preoccupied perhaps more than any other writer of his generation by the larger literary game, by who is winning and losing, and goes on to cite Amis's novel on the subject, The Information. As for Roth, a writer known to take an active part in his own jacket designs, Cowley calls him 'disingenuous' for allowing himself to be represented on his latest by merely a long list of prizes won, an act which Cowley calls 'an exercise in self-aggrandisement'.

But surely, in relation to Amis, the point is that it is those who fall on the wrong side of a cultural situation (Amis is famously not a prize-winner) who know best its iniquities (and will be obsessed with them)? And if, as Cowley says, prizes have a stranglehold on our culture, then an understanding of the iniquities does not free anyone, including Roth, from the trap. Cowley thinks there is a sense of presumption in not noting where or when the writer was born: as if to say, 'You know exactly who the famous and excellent Philip Roth is, he needs no introduction.' Instead, we are told only what he won, as if past achievement validates the present offering. Well, excuse me, but, against the grain of the cult of personality, I think a writer's literary history is more important than his personal one...

But then at the end Cowley tells us this about the prize culture: ...it shouldn't be taken too seriously, and one wonders how serious he himself is being. This is his reason: no one now has heard of the first Nobel Literature prizewinner, Sully Prudhomme, who won that year over Tolstoy. But, to take his earlier argument further, it's a different culture now. In this era of remainders and the slashing of backlists, would Tolstoy's books remain on the shelves nowadays long enough to become classics, or would they have been binned, as he tells us Lionel Shriver's were before she won the Orange Prize?

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Tagged, Memed, Caught Out Again

Last week Debi Alper, who has a fabulously witty blog, tagged her thus: Five Things Feminism Has Done For Me. Well, this is what feminism has done for The Bitch:

1. To make her stick to her own agenda (fiction and publishing, not feminism!).

2. To make her set her own rules (five things be blowed).

Today Roger Morris zaps her: Eight Things About Me.

What???? Well, here goes:

1. Far from wanting to reveal eight things about herself, The Bitch would still be anonymous if Blogger hadn't undone her (for The Bitch's anonymity was in part an attempt to underline her view that in our present cultural climate words and ideas are subverted to image and personality).

2. Even on her writer's blog The Bitch tries to stick to professional matters, though she knows she's not successful, and anyway being professional means using images etc in just the way she critiques here.

3. The Bitch once ate for breakfast a literary agent who wanted to sell her fiction as autobiographical.

4. The Bitch once ate for tea an editor who ditto.

5. The Bitch keeps a bullwhip ready for when newspaper journalists come calling and ask to go to the loo and go through your cabinet.

6. Schooled from the age of five, The Bitch has never, ever allowed anyone to misquote her

7. or judge her work by her life.

8. The Bitch is a writer of fiction. (Geddit?)

And now I'm supposed to tag someone else. How about Ms Baroque, Fessing Author, Alias Lucy Diamond , nmj, and Bournemouth Runner at The Art of Fiction (and they can choose either meme or none at all..)

The Bitch Munches her Words

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Thanks for Sharing

Last night she went with The Partner to a reading by the Irish poet, playwright and novelist Sebastian Barry. Now Barry to The Bitch's mind is a quite brilliant writer, a writer after her own heart, one of those you read and get the quite spooky feeling that he's written what you might have written, or would have written if you could/in another life, or already once did in a previous life etc, etc. Turned out he's a brilliant reader as well, which so few novelists are, and The Bitch was bewitched, and, as he read from his latest novel A Long Long Way, laughing and in tears.

Then he turned to one of his plays and read a long tale-telling speech from near the end about a dog and a ewe, which he pronounced, exactly as the Bitch's Irish father did, 'Yo'. The Partner gave The Bitch a nudge, and she knew what he was thinking: about the tale her father always told of the time he was eight years old but not at school because his parents were so poor, and the schoolmaster happened by and asked him if he could spell ewe, and he could, so after all he went to school, paid for by the church... It's one of those little incidents from real life I've pleated into the made-up rest of a novel of I've just written.

Well, then I went to get my copies of Barry's books signed, and I told Barry what a brilliant writer I thought he was, not caring if he thought I was a suck, and he looked ridiculously pleased, and it was like some kind of literary love-in. And then The Partner, who was standing right beside The Bitch, said,'Tell him about your father's ewe.' For god's sake! (These people at signings, wanting to come up and identify, and tell you their life stories!) But Barry was looking curious now - or was that glazed? - and out of embarrassment, The Bitch told him.

A strange look had come over Barry's face. 'What church was that?' he wanted to know. 'What town was it?' The Bitch answered in embarrassment, feeling possibly patronised - for god's sake, it was meant to be just a throwaway anecdote! She began to leave (to make a hasty retreat) and Barry said, his face impassive: 'Don't be surprised if you come across that incident in the next thing I write.'

The Bitch jumped like a scalded cat. 'You can't! I've just put it in my novel!'

'We'll just have to see who gets there first.'

'But that's not fair! You've got a publisher, and I haven't yet!'

His face was bland, beatific. 'It never is fair.'

'Bastard!'

His grin was impassive, enigmatic.

I think he was joking (why the hell would he want my silly little anecdote?). But just in case: YOU READ IT HERE FIRST.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Voices and Ears

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Uncreative Writing

Interviewed today in the Guardian by Laura Barton, Booker winner Kiran Desai points out one of the problems: They demand you write a certain way because you have to present your work in half-hour instalments. You are having to polish only a little bit of it. It suits the short story more than the novel. She could never have written her 'monster' novel under these circumstances, she says.

The Bitch has often guiltily thought that it's nigh on impossible to write any novel under these circumstances. In particular, novels which play narrative games with readers' expectations simply don't lend themselves to the piecemeal week-by-week judgement of others' expectations. But for any novel to be unified and organic, you usually need to get to the end before you can know precisely how to hone the beginning, after all.

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Too much experience?

...the publishing market treats novelists as promotable contenders with their first and second books, mature talents by their third, and burned out with their fourth and subsequent titles. This year's passed-over favourite, The Night Watch, was a fourth novel [and from the only established author on the list].

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Short and Sharp

http://books.guardian.co.uk/digestedread/story/0,,1891754,00.html

Monday, October 09, 2006

A British Sporting Event?

The winner is JM Coetzee, with Disgrace (in good old colonial style The Observer, 'following the Booker', decided to define 'British' as including 'Ireland and the literary traditions of the Commonwealth'); 2nd place goes to Martin Amis's Money, and joint third to five novels: Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess, Ian McEwan's Atonement, Penelope Fitzgerald's The Blue Flower, Kazuo Ishiguro's The Unconsoled, and Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children. Joint eighth place is shared by Ishiguro (again) (The Remains of the Day) and John McGahern with two novels, Amongst Women and That They May Face the Rising Sun.

This is not a readers' poll. If this poll has any consequence, McCrum opines, it derives from the fact that we have consulted with mainly professionals. Ah, that best of British... Those polled were writers themselves and critics. Well, I have recently argued that writers are excluded from debate about the meanings of their work, but this is not that kind of debate. It does not appear to be much of a debate at all, but just another of those winners-past-the-post British exercises, pitting different kinds of writing against each other in the pursuit of some kind of mythical pinnacle.

What does it all mean? McCrum feels that his wider trawl through the 'Commonwealth' makes The Observer poll more culturally inclusive than the similar American poll conducted last spring, but putting culturally diverse writings in competition with each other, in which some will 'win' and some won't, is surely to operate exclusivity. I notice some names missing from the list of those polled - apparently some declined, for these sorts of reasons - and isn't it obvious that writers, understandably, might well gun for the kind of writing which includes their own? (One would never want to accuse anyone of voting for their friends, of course!) And does it mean anything that, although the list of voters is almost half women, only one woman makes it to the first eight, and out of 51 runners-up only 18 are women? (What, so it's true, then: women's novels are less good than men's? Or no: women novelists are still in awe of the men while the men aren't so thrilled by the women? Which?)

And some of the names missing from the list of voters? Well, actually, JM Coetzee, Martin Amis, Ian McEwan and Kazuo Ishiguro. Is there some kind of poetic (or novelistic) justice going on here?

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Rub those pound signs out of your eyes...

http://www.gawker.com/news/unsolicited/unsolicited-why-you-dont-want-a-big-advance-203569.php

Thursday, October 05, 2006

Selling Words

fancy photomontages:

fancy photomontages:  and towards the end, big bleed photos:

and towards the end, big bleed photos:

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

How to Sell a How-To Book

Taylor's main point is that these books, aimed in the main at reading groups, reinforce, through their choice of novels for discussion, 'the stranglehold exerted on literature by the three-for-two promotion and the high-street discount'. Thus, he says, they contribute, in a way which would probably horrify their authors, to the 'homogenisation of our literary culture.'

He has a point, I think. The Bitch is in a reading group whose members pride themselves on being immune to hype, and on forming their own opinions without recourse to others - black looks for any fool who brings to a meeting reviews downloaded from the internet. But if these How-To books would never sell to my lot, they are clearly selling to someone. And anyway: which books come to mind when my independent, stroppy lot are thinking of books for discussion: why, the Booker shortlists, of course, the books they've seen in three-for-two promotions - they're the only ones they can be expected to have heard of, after all.

And if these How-To books didn't feed into the expectations of reading groups, how would they sell?

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

Don't We Just Love a Scapegoat?

As an agent, I feel quite strongly that Frey was shafted by his publisher and agent. Not only must they have known that embellishment was going on, they *did* know - I met an editor at Doubleday who told me, prior to the book's Oprah laurels, that he was sure some of the book wasn't true. It is deeply disingenuous of the professionals closely involved in the book's publication to claim they were duped by Frey, ruthless of them to drop him, and deeply immoral for them to continue to profit from the discredited works which they are merrily doing.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Authors and Authority

The event was a prize-giving, the culmination of a competition run by an organisation whose main activity is running short courses and workshops for writers. A founder tutor and competition judge announced the prizes, in some cases inviting the author to read, and in every case talking in some detail about the winning work.

My artist guests were both fascinated and shocked. Firstly, they were fascinated by the thing I have always taken for granted, the spectacle of authors getting up and reading out their work aloud, sometimes with confidence, sometimes visibly shaking, sometimes reading well and sometimes not so well. What struck them forcibly, as contemporary artists trained to create work in such a way that it speaks for itself, was that the author was thus forced to be in the way of the writing, and the writing itself thus subsumed and ultimately divested of authority. This is obvious when the reading is bad, but it's true even if the reading is good, and of course it's true even at a famous author reading, where the whole thing plays into the cult of personality.

More importantly, however, the thing which shocked the artists was the compere's commentary. Trained in London art schools to take full responsiblity for the meanings of their work and, to that end, to control the context in which it appears, they were staggered that writers could be in a position where another person could decide independently what their work was about and announce it to the world, while the author had no opportunity for speaking about his or her work. Well, I laughed at the time, the judge was after all saying pretty nice things, and I was one of the winners, and it doesn't do to look a gift horse in the mouth, but it's true that when he said my story was a 'rite of passage' piece I was pretty gob-smacked for a moment, and couldn't work out how he made that out, and later when I did it struck me that, much as he'd liked my story, he may well have missed the point.

And afterwards it set me thinking. Clearly we can never expect to have ultimate control over how our work is read - books are ultimately what readers make of them - and clearly sometimes authorial intention fails to be realised, but writers do sometimes do new things which need to be read in new ways. Yet it does seem that on the whole it is the writers who have least voice in any debate about their work. One of the biggest crimes, for instance, has always been for a writer to take issue with a newspaper criticism (so undignified!), and now, it seems to me, the whole creative-writing teaching explosion has led to an ethos in which the authority on the meaning of a writer's work is not the writer but another (the teacher). Interesting that while the teaching of art has so much longer a history than the teaching of creative writing, artists do not suffer this situation. And look at James Frey, apparently utterly without control of the context of his work, and when he tells the Guardian that he first wrote his book as fiction, he may as well have said it into the wind, for there's John Burnside writing in the same paper last week, making the argument I have made about different kinds of literary truth, but nevertheless overlooking this crucial point.

Ironic, really, when you think of why we write in the first place...